Greg Galeazzi in his Hopkinton home with his wife, Jazmine, and daughter, Amelia.

Photos by Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

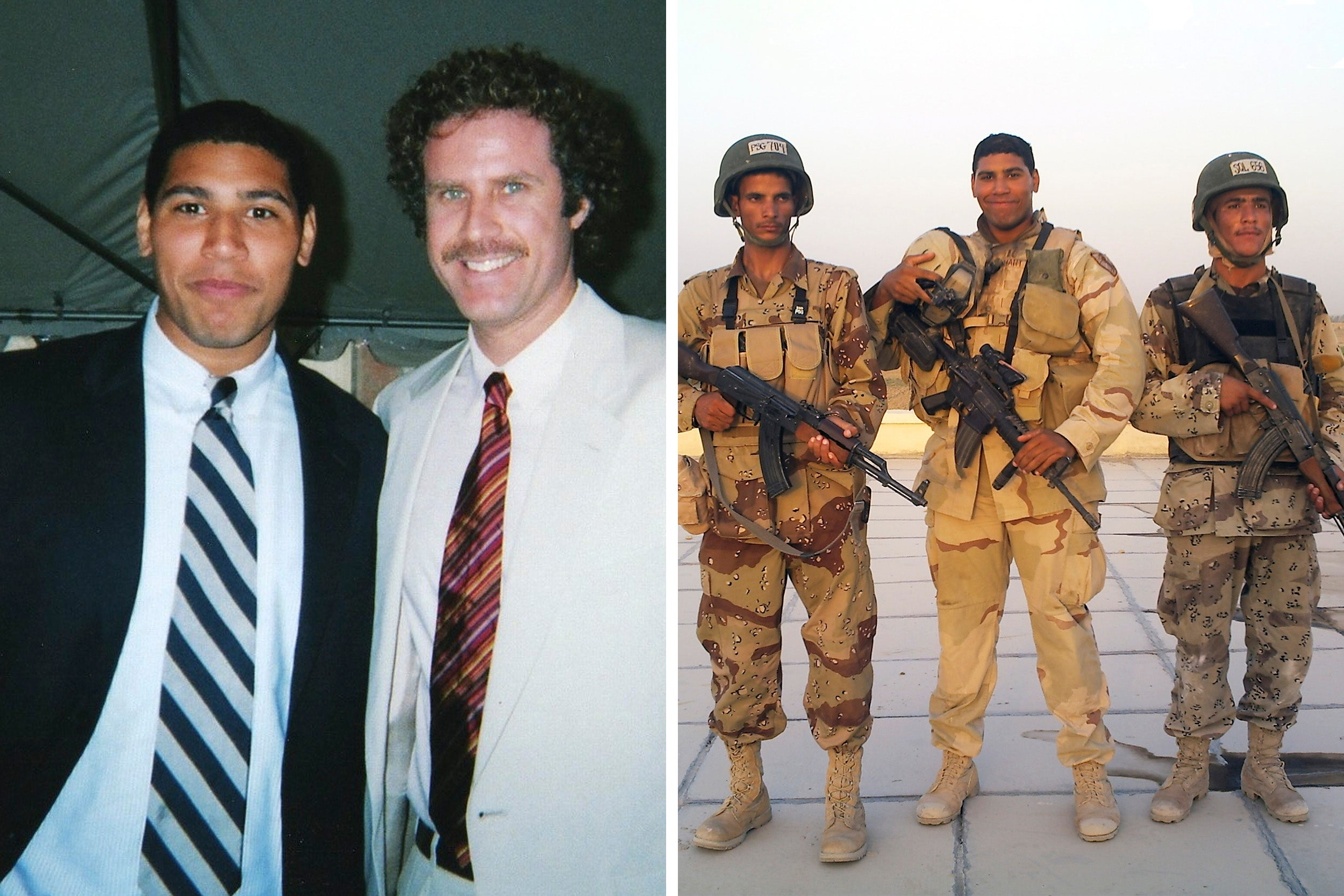

Between Army and Medical School, a stop in hell

Veteran who lost legs in combat reflects on Afghanistan service and decision to become a doctor

Greg Galeazzi is a double amputee who has made his peace with combat injuries suffered in Afghanistan in part by seeking to help others through a career in medicine. The former U.S. Army captain is now a fourth-year student at Harvard Medical School, applying for residency programs in physical medicine and rehabilitation. In a conversation with the Gazette, he talked about the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, his service there, and the connection between his injuries and his approach to medicine. The interview was edited for clarity and length.

Q&A

Greg Galeazzi

GAZETTE: Could you share your reaction to the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan?

GALEAZZI: I definitely don’t speak on behalf of all veterans and I haven’t been in Afghanistan since I was medically evacuated following my injury in 2011. Other than seeing what’s on the news, I don’t have any insider info regarding what’s been going on recently. That said, I support us pulling out of there. From what I’ve seen on the news about the Taliban sweeping back in and Afghan security forces fleeing or surrendering — if not outright aiding the Taliban — and government officials not really doing much to step up, that sounds a lot like the majority of the Afghan security forces and Afghan government officials that I encountered during my one-year deployment in 2010 to 2011.

When I was there, we were already 10 years into the war. Security forces were equipped with uniforms, vehicles, and weapons. Politicians paraded around and held meetings. But I couldn’t help but feel like they were going through the motions. Aside from a couple of motivated individuals here and there, most of the Afghan security forces and government officials I worked with seemed to have little interest in taking the reins and leading and securing their own country. It was almost as if they didn’t think the Americans were serious about leaving someday. I remember thinking if nothing changes over here, if the Afghans themselves don’t start stepping up, this country is going to collapse as soon as we leave.

GAZETTE: Was part of the problem that we just didn’t understand the culture in Afghanistan?

GALEAZZI: That’s definitely a major part of it. The challenges in Afghanistan are complex and multifocal, and within their own population there are numerous tribal affiliations, each with their own cultural identities and languages. We were attempting to establish a Western-style central government to lead a country with little semblance of a common and unified national identity. Often, it seemed like our objectives simply didn’t align with their hopes for the future. We were focused on setting up a legitimate government, with fair elections, modernized infrastructure, and a competent military. But those concepts were quite literally foreign to most Afghans, and many seemed rather content with a simpler way of life. While the U.S. had these grand and noble ambitions, most of the villages I encountered had never even heard of Osama bin Laden or the 9/11 terrorist attacks. They didn’t know why we were there in the first place.

“But as I recovered, as I grew stronger, as I regained my independence and adopted a new way of life, suddenly these things weren’t off the table anymore.”

GAZETTE: You were injured the same year U.S. forces killed bin Laden in Pakistan. Should our mission have concluded then?

GALEAZZI: It’s hard to say. In my mind, our initial mission was revenge, payback, justice, whatever you want to call it. Those were the underlying factors that drove the American government and the American people to support sending troops over there. But the mission became less clear in the 10 years that followed the invasion, and our objectives snowballed well beyond delivering justice to those responsible for 9/11. By the time bin Laden was killed, we were embroiled in a lot of different things and I don’t think it would have been an appropriate time to leave. We had a lot of loose ends to tie up, and with bin Laden dead, I think there was renewed hope that progress could be made.

GAZETTE: Your injury was caused by an IED. Can you describe what happened?

GALEAZZI: I was serving as a platoon leader at the time — a position I inherited after the previous platoon leader, 1st Lt. Mark Noziska, was killed in action. We were returning to our base following a routine daily foot patrol in rural farm country outside of Kandahar. Insurgents detonated 30 to 35 pounds of homemade explosives below my feet. It took off both legs immediately. I sat up after hitting the ground thinking maybe I had a broken leg or something. But both legs were gone. I was actually classified as a triple amputee because my right arm was almost completely cut off, though they were able save that despite nerve, bone, and soft tissue damage. I have no elbow, the right arm is totally fused. I can’t bend it and there’s a lot of nerve damage in the hand. But I have some sensation and motor function in my hand, and mostly use it as a supporting limb now. I used to be right-handed so I had to relearn how to do everything. Shaving, eating, writing, all that stuff.

Greg Galeazzi spends time with his family.

GAZETTE: You had about 50 surgeries, hundreds of hours of physical therapy, and spent months in the hospital. Did your time as a patient influence your decision to pursue a career in medicine?

GALEAZZI: Oh, yeah. I had already been leaning toward a career change into medicine before I deployed. I was never planning on being career military. My undergrad degree was in business, but I wasn’t sure I wanted to do that. Medicine checked a lot of the boxes in terms of what I was looking for in a career. Then I got injured and for the first year or two, I focused on my recovery. In those first few weeks, I didn’t really have the strength to even sit up in bed on my own. Simply going to the bathroom was a team effort. So trying to imagine returning to any sort of independent life, let alone going to medical school, was completely out of the question.

But as I recovered, as I grew stronger, as I regained my independence and adopted a new way of life, suddenly these things weren’t off the table anymore. Maybe there are some things within the field of medicine that will be physically challenging for me, but for the most part, I don’t need my legs to be able to assess your symptoms or listen to your heart and lungs. I realized there’s still a lot that I can do. It became a goal, and gave me a renewed purpose to live, to get stronger, and motivated me through the most challenging days of my recovery.

GAZETTE: Will the experience affect how you deal with patients?

GALEAZZI: It already does. My clinical work as a medical student has landed me in countless scenarios where I was better able to connect with patients when others could not. It has afforded me a perspective on life and insight into human suffering that help me to understand my patients, and as a result, provide them with better, more personalized care. If I can use all the suffering that I’ve gone through, all the pain, all the sleepless nights, the depression, all the medications I’ve been on, procedures, you name it — everything I’ve gone through — if I can use those experiences to be a better doctor and maybe make a positive difference in someone’s life, perhaps all that suffering will have been worth it.